Lecture at the 5th IHVO-Symposium on the 22nd of September 2012

by Hanna Vock

Gifted children learn many things

-

- earlier,

- more intensely,

- in more detail.

Many things come easily to them.

… in a nutshell …

In her lecture the author exemplifies 8 requirements to be fulfilled for the gifted child to learn.

Since many gifted children can hardly be motivated extrinsically (by external incentive) they are extraordinarily dependent on the fulfilment of these preconditions for learning if they are to develop their full potential.

Why is this so?

This results from (1) their high intelligence and (2) their extraordinarily great motivation to learn.

As to the high intelligence of these children:

-

- Their readiness of mind consists in their ability to assimilate large amounts of information, which they then process very quickly. They are also very proficient in integrating new information in already existing networks of cross-linked contents.

-

- From of a vast amount of information their excellent memory reliably distinguishes the important data that are vital for their current learning process. These essential data are reliably stored, and retrieved easily when needed.

-

- These children are especially good at recognising patterns and principles within an abundance of information.

-

- Their vivid imagination lets them produce a steady stream of ideas. The questions they come up with are to be looked at as ideas too. Their inventiveness is often paired with an early ability to evaluate and criticise their own ideas and those of others. They do not only have many ideas, they have many good ideas.

-

- They are good at relating separate pieces of information to each other and making the right connections.

These statements are based on the Berlin Model of Intelligence Structure (BIS) which is widely accepted as the most advanced concept of its kind.

See: What is Intelligence?

Aside from intelligence I had mentioned the extraordinary learning motivation, which characterises these children.

Once you know one of these children well enough, you can easily recognise several simultaneous learning processes at any given time. These occupy them steadily, even though nobody told them they had to learn just that right now.

As long as their learning motivation is not destroyed they will constantly be involved in learning projects – some of which may go completely unnoticed sometimes.

However, we do also know some gifted children who have become so-called underachievers. These are children who have lost the desire to learn or who cannot get themselves to learn what they are expected to learn at the time. Underachievers, young and old, are sad individuals, oftentimes rebellious on the outside and desperate inside.

It therefore pays to investigate with some scrutiny what exactly it is that sustains or destroys gifted children’s desire to learn.

A general rule is:

The desire to learn is preserved if the learning environment is right for the learning individual.

– A child who is constantly challenged too much looses the desire to learn.

– A child who is constantly underchallenged looses the desire to learn.

– A gifted child, who learns in its own creative ways, looses the desire to learn if it is forced into an inadequate, inflexible and unimaginative system.

If we succeed in preserving the child’s desire to learn and support the child adequately, it will inevitably show great performance. This performance may not show exactly when it is supposed to nor will it necessarily be pertaining to the given subject matter – yet, over time the child will acquire vast knowledge and great skills.

It is important to have this confidence in the gifted child and to keep it up!

What does it take for children to remain “learners out of desire”?

Mankind’s knowledge about the conditions that are conducive to successful learning has been expanded greatly in the recent past. I will try to compile the essentials in 8 points:

It has been shown scientifically that learning processes will be successful …

-

- (1) if they take place in an cheerful and concentrated atmosphere and without fear,

-

- (2) if there is delightful interest or at least an inner readiness to deal with the given subject matter,

-

- (3) if the contents build on already acquired knowledge and relate to present abilities which can be put to use in the current learning process,

-

- (4) if it is comprehensible for the learner what this particular knowledge or this particular skill is useful for,

-

- (5) if learning is part of a project whose success means something to the learner,

-

- (6) if the result of a particular learning process leads to social recognition,

-

- (7) if there is satisfying, possibly even inspiring, exchange of thoughts while dealing with the subject matter,

-

- (8) if another person supports the learning process by virtue of his or her own personal and professional authority and – even better – by showing his or her personal enthusiasm for the subject matter.

These 8 points circumscribe – in general – good preconditions for learning.

Needless to say, they apply to gifted children just the same.

Startlingly even, gifted children – as opposed to other children – need all of these preconditions to be fulfilled, because they can hardly be motivated extrinsically. Other children can be motivated to some extent by pressure or incentives (even though this does not render the same success as if all preconditions were fulfilled) – but gifted children will fall way behind their potential if as little as one of these requirements is not met. They do not necessarily all become underachievers then, but they will not even get close to their possible achievement levels, which is frustrating – while with all requirements met, they will effortlessly perform at the highest level.

I will now shed some more light on the individual points. And while I do so, the reader may ask himself: When and how are these requirements for good learning met in kindergarten and in primary school?

About 1:

Learning processes will be successful if they take place in an cheerful and concentrated atmosphere and without fear.

What could learning children be afraid of during the first ten years of their lives, that could partially or almost entirely incapacitate them?

They could be afraid of failure, punishment or embarrassment.

Let us look at the fear of failure first. It can be tormenting.

Failure means not to succeed in completing a given task (possibly under time pressure). Every person has to learn how to deal with the fear of failure. For all our lives we will never be beyond the possibility of failure.

Gifted children oftentimes set problems for themselves; sometimes they do not meet their own expectations, which makes them feel like failures while the kindergarten teacher finds the performance OK or even good. There was, for instance, a 4 years old girl in my group, artistically very talented, who almost daily drew wonderful pictures, yet tore them to pieces almost every time, because she thought they were “crap”.

Whether or not the child has failed in a given situation is in the eye of the beholder. There are those who evaluate a performance from outside and there is the child itself, feeling like a failure. As demonstrated by the above mentioned example a gifted child’s assessment of its own failure often diverges from that of the external evaluation. By the same token there is the opposite case where a child focuses on the core aspect of a task while neglecting secondary aspects like “neatness” and additional features. Then the child may be quite fond of its performance and yet experiences that contrary to its own expectations the work is not appreciated, because the beholder applies different criteria (which the child may find irrelevant or unimportant).

Whether or not a child regularly fails to fulfil the given task is, that is whether it fails regularly, is of course also dependent on the kinds of tasks it is given.

Whether or not a child experiences the fear of failure regularly, depends on its own expectations as well as on the demands made on the child by others. This is one more reason that it is important to always be well aware of the general and current potential of the child.

If, for instance, a child who is not gifted, were mistakenly considered gifted, its environment would cause plenty fear of failure with their inadequately high expectations, thereby incapacitating the child.

Fear of Punishment… should have become obsolete in our society – but not so. Every single bad mark at school is a penalty imposed by the system “school”. And many bad marks (where some will consider a “C” a bad mark) will be followed by further penalties (mostly introduced by misguided parents, and often by the misguided school system too: it imposes: repeating the school year, remedial lessons, private tutoring). All this is meant to help, but it also spells the unspoken message “you didn’t cut it”.

Fear of embarrassment is a widely underestimated fear (with regard to children). “I blew it (again), and everybody saw it.” (For example when trying to jump across the box.) Or: “I’m so ashamed. Again I couldn’t give the right answer.” None of the sweet talk and encouragement will do gifted children any good if they are their own fiercest critics, even when they are still very young.

Children who are not very successful in the system “school” defy this fear of embarrassment by devaluating the relevance of success at school. This is understandable and serves their psychological self-protection. Sometimes this is a collective phenomenon seizing a whole class. Those gifted children who have an easy time learning at school are simultaneously down-graded as “nerds”.

Even at kindergarten we have to be ready to deal with the fear of embarrassment. Gifted children do at an early stage in their lives begin to compare themselves with the other children and even with adults. By the same token (because of the early development of certain intellectual capacities) they are early judges of their actions, comparing the results with their high expectations.

Some people say: “I work best when I’m under pressure.” (For example when a presentation is to be prepared.) Preparing a presentation is a big and laborious learning process with an uncertain outcome. Yet, it must be turned in at a given time. Unpleasant feelings may lead to repeated procrastination – or interruptions once one has started. And then one does get it done at the last minute. So, is it not true that one can work best under pressure?

No, it is not. One would certainly have learned a lot more in the process if the work had been started early and carried out joyfully and continuously, investing more time.

Shortly before the deadline is up and pressure rises, most people – certainly not all – do manage to suppress the unpleasant feelings enough to get the work done.

What are these unpleasant feelings which slow us down so much? It is the fear of failure, paired with the fear that the effort might in the end be in vain (haven’t finished, didn’t get to present it, was evaluated negatively or unfairly). Or maybe we have the feeling that we are doing something pointless that does not have anything to do with our own life or interests and will end up in some folder and will eventually be thrown away without ever having had any impact on our life.

With regard to kindergarten this seems to imply to me …

-

- that any kind of laughing at a child (for failing) must be prevented and termed a downright meanness for all children to know;

-

- that the informal presentation of ideas and results should be a regular part of everyday life in kindergarten;

-

- that as a precautionary measure we should talk about the fear of failure and embarrassment with the children who are ahead in their intellectual development.

About 2:

Learning processes will be the more successful the more there is delightful interest or at least an inner readiness to apply oneself to the given subject matter.

Delight and learning are two things which to most adults seem not to go together well. Yet, when watching 1 year old children, their delight in doing things and in learning is most obvious to see and to hear. They are laughing and squeaking for joy. Even when extremely immersed in an activity they still appear joyful. For us adults the term “flow” had to be coined for describing the blissful state which many – if unfortunately not all – people sometimes experience.

The English word “flow” has become a technical term in psychology and it is to express that “everything just seems to flow easily and all by itself.”

“Flow” in this sense is a state of great and delightful focus on an interesting activity. This state of mind occurs in direct connection with rapid learning. While experiencing this “flow” – young or old – one is learning new things.

If intensive learning processes are to be initiated, flow must be brought about.

How to do so?

We have to offer something exciting, inspiring which will electrify the children. One might call it inquisitive learning, experiential or adventure pedagogics. Playing and learning with joy, addressing all our senses.

When exactly do most people lose their enthusiasm about learning?

-

- If they are kept in unnecessarily regulated, poorly organised, uninspiring surroundings populated by uninspired, permanently bored or unhappy contemporaries.

This can be their own family, the neighbourhood, the kindergarten or school. Unlucky children will find themselves in such surroundings from their first day of life. They will learn little if anything, certainly much less than they could.

- The enthusiasm for learning will also be lost if children are to fulfil tasks taken from an anaemic curriculum that is far from all matters of real life.

What is laziness?

This question pertains to the point of enthusiasm for learning. It is often heard: “He is really quite smart, but just too lazy for learning and accomplishing anything.”

So then, what is laziness?

For the individual so termed it is the lack of motivation and the inability or unwillingness to overcome this and get busy anyway.

If bad comes to worse the lazy one will readily take the blame and the disadvantages for not having done something, for instance for not keeping something tidy.

The others take a different angle:

Laziness is the unwillingness to simply do what is expected, even though it is (in the eyes of everybody else) a necessity. We criticise the lazy person for not pushing himself.

The lazy person indulges in a freedom we do not grant ourselves: he resists. That, too, makes us angry.

But it pays to take a closer look and see the differences.

These are five rather different cases:

1.

A father who is unreliable in his job, who keeps getting up too late and jeopardises his employment. = This is considered unacceptable, regardless of what possibly tragic developmental background there is to it.

2.

A man, who has never in his life cleaned a window. = This is socially accepted as long as someone else takes care of the cleaning. There are many men and rich women who have never cleaned a window – in the case of not so rich women this is a different story. This shows how social acceptance is granted unequally.

3.

A woman who has never in her life laid out nor tended to a vegetable patch because she just absolutely does not feel like it. = socially this is perfectly acceptable in our day, it would not occur to anybody to scold this woman for being lazy. In former times, when most women were working on farms, they would have been criticised heavily. Whether or not a certain kind of refusal is accepted is therefore strongly dependent on the respective culture.

4.

A child whose hand writing is illegible and who refuses to practise writing legibly, even when being told that writing only makes sense if the written words can be deciphered. = The child will not submit to the argument. It will not show insight. That means: It will have to face the consequences: namely having a bad handwriting and getting bad marks at school. Should the child be allowed to make that choice? Or should it be forced? I am strongly opposed to forcing anybody to learn. Enforcement violates human rights, and besides, it is unproductive and destroys creativity. After all good reasoning and arguing I will have to accept the child making its choice. Unfortunately this is hard to do, primarily for many mothers. They raise the pressure and continue the lament, which, of course, kills everybody’s nerves.

“The truly lazy person indulges in laziness without falling prey to it”, says Jack Chaboud in his “Petit Livre de la paresse” (Little Book of Laziness).

Many gifted individuals have a good sense of just how much laziness they can get away with when it comes to learning processes that do not interest them. Others will fall prey to their fears and inhibitions, failing to attain important degrees and thereby missing out on the chance to live a life which is in accordance with their giftedness.

5.

And finally we have a child attending the first form who is unwilling to perform the preliminary exercises for writing. = The child will not submit. Does it have the right to disobey? Does it have a sense that it can learn to write legibly without these tedious preliminary exercises? It should be encouraged to try these exercises.

Imagine a gifted child who has drawn many imaginative pictures because it has so far lived a happy life with many wonderful playing experiences and who has had the leisure to lay down these experiences in imaginative pictures. A child that may even have sung a lot of songs because that is what it grew up with. This child has developed fine motor skills and a good feel for rhythm, it does not need preliminary exercises for writing – neither before nor at school. They would be utterly pointless for this child, entirely unproductive.

A wise sentence by Laozi goes: “Doing nothing is better than going to great lengths and accomplishing nothing.”

Yet, even an extraordinarily talented child who has not spent so much time drawing will learn how to write letters best by writing texts which it finds important. In such a somewhat casual learning process it will improve the legibility of its writing if the addressees of the texts hint at illegible letters in a friendly tone. But for this the respective tutor (be it the mother, the kindergarten teacher, the school teacher or whoever) will have to take the time and repeatedly communicate with the child in writing – and that person must be able to accept the initially crooked characters with great equanimity.

What is more fun?

“Come on, let’s write another letter.” Or: “Practise a couple lines of B’s.”

The American writer Thornton Wilder quotes another Chinese aphorism:

“The serene make better use of their chances than do the driven.”

About 3:

Learning processes will be most successful if they build on what is already known and if they tie in with already existing abilities, which can then be utilised in the learning process.

The better I know a child, the more I have done together with the child, the better of an assessment I will have of the child’s abilities, so that I can take it from there.

In order to get to know the child I have to do things together with the child. I see little of the individual child’s abilities if it “vanishes” in a group of 15, 20 or even 30 children.

I make observations while we do things together. If, for instance, I take two children aside to bake a cake with them while I let the rest of the group play freely. I will afterwards know which of the two children is able to crack an egg. I also notice which of the children has an idea of the process as a whole and which one only sees separate parts of the process. Another thing I see is to what degree the children understand numbers and amounts and whether they can distinguish between flour, salt, sugar by appearance and taste.

I also see to what extend the children have been able to develop the ability to collaborate.

If I am not sparing with words I will find out whether the children know where flour comes from and what organic eggs are.

Such shared activities will bring forth ideas for further activities, learning areas and projects.

What I have seen during such a shared activity with two children I can memorise short term and make notes of it later on.

If, on the contrary, I bake a cake with 10 children I will be busy keeping up a certain degree of order, deciding who gets to crack the four eggs … And I have to keep the frustrated children involved when they do not get to do things themselves and who are trying to enter a peaceful intellectual exchange with each other and with me.

In that case I can proudly say that I have offered an activity for 10 children, yet there has been less progress for each one of them than there would have been in a small group of 2 or 3 children.

What’s more, I will not be able to say much more about the children than: P. likes to push to the front, L. keeps low key and F. horses around. I do not gather any substantial impression of the children, instead I make random observations, which may not serve for much more than reinforce prejudices and which I will probably forget pretty soon anyway, because I cannot dig any deeper in the given situation.

Which mode of work is more satisfying for the individual kindergarten teacher? Everybody will have to decide for himself. This is not to say that satisfying and fulfilling learning experiences in bigger groups are not possible.

Entirely ineffective for learning are school classes. There I have more than 20 children, but no assistant to take care of part of the group while I am working with the other part. Sometimes I wish pupils had little traffic lights on their foreheads: green for a child listening with interest, yellow for children barely paying attention and red for children who are not following at all. I am afraid in many classes there would be nothing but yellow and red lights for extended periods of time.

If on dark winter days the head lights at the ceiling only went on whenever the teacher himself is experiencing joy and flow at work, many classes would mostly sit in darkness.

With the organisational structures at school currently in effect it will take very long until a subject teacher, tending to 130 children in 5 different classes, knows his pupils, their abilities and interests well. Often this fails altogether, and the name of the pupil is pretty much all that comes to mind. No wonder individualised teaching hardly ever happens.

But not only subject teachers have this problem – even the form teacher at primary school does not really come to know very much about all children. At best she can come up with an assessment of the child with regard to current learning matters, but how much does she know of the child’s intellectual life?

So: Intensive activity with few children makes for more effective learning than do activities for the whole group.

Can this be conducted in kindergarten? And how frequently will I be able to work in this mode?

Working in small groups is something that everybody has to push for and implement himself. I personally, during my active time in day care, soon could no more do without working in small groups on a daily basis. Of course, the groups would change all the time. One day I would sing kindergarten songs with the 4-year-olds and discuss the lyrics so they would soon be able to sing them by heart (that would take no more than 15 minutes on a few days), another time it was scientific experiments for the brighter children, which could easily take the entire morning until noon. My colleague had the same right to offer small group activities and oftentimes I noticed her (a childcare worker) having deeply philosophical discussions with two children while playing a difficult game with them.

And then these small group activities were also integrated into and played an important part in the larger projects that addressed the whole group and covered greater periods of time.

I cannot imagine advancement of the gifted in kindergarten without small group activities. Integrative Focus Kindergartens are by virtue best tailored for the advancement of the gifted since these kindergartens have more gifted children than statistically expected.

(Remember: About 2 – 3 per cent of all children are gifted. With 80 children at one kindergarten that would with all probability mean one lonely gifted child.)

The older the gifted children are, the more they should have other gifted children around them to learn together with them.

About 4:

Learning processes will be most successful if the learner understands the reason for learning the given subject matter and what that knowledge or ability is going to be good for, i.e. how it is going to be useful.

Why are we going to visit the fire brigade? Why do I have to learn the rule of three in mathematics? Why should I practise writing numbers? Why am I supposed to practise tying my shoes? (My shoes have Velcro strips!)

Let’s stick with the fire brigade example. What is the children’s knowledge and skill before and after? How is the topic tied into everyday life in kindergarten? It does not make sense to visit the fire brigade before the children know what fire really is, how beautiful it is, but also how hot and dangerous it can be, what a fire hazard may do and how a child should handle fire.

If you will not even let a child light a candle you might as well skip the trip to the fire brigade too.

Kindergartens are expected to take the children to the fire brigades, but it would not occur to the parents of these same children to make a camp fire with them. This is how the children’s knowledge remains superficial and disconnected from their own experience. No wonder their interest and focus is rather flat. And then the gifted children among them are often left frustrated because with 15 or 20 children jumping about two fire fighters they hardly get a chance to get into a prolonged dialogue of questions and answers (as they naturally would).

About 5:

Learning processes are most successful when learning happens in the course of a project whose successful completion is meaningful to the learner.

A 5 years old boy taught himself how to write on the computer using MS Word, because he wanted to make a picture book – a real one. For him it was time to learn the use of a word processing software right now in kindergarten (something that otherwise occurs in secondary school), because he was convinced that he needed it now. He quickly understood many options of the tool and learned how to use them.

It felt entirely natural to him, it was part of his project and cognitively he was able to handle it too.

Not much unlike when my colleague had the idea to teach the children how to tie knots. It was boring for the children as long as they did not need this for their playing activities. But one day they started building little huts with rods and blankets, which they needed for their game, and they realised that knots might be quite useful.

Most of the children were content with simple or double knots. The three gifted children and two of their friends, however, really got into it, and learned sailor’s knots just from drawings. The difficulty was challenging them and the cool knots were the best of it all. Even if in the end only two of the three gifted children stuck with it all the way to the really heavy duty super complicated knots.

So: Let’s initiate and support interesting exciting projects, that’s how children learn.

About 6:

Learning processes are most successful if their results lead to social recognition.

-

- The performance of a stage play being appreciated by the parents’ applause.

- An art project whose results are presented in an exhibition and then sold.

- Potatoes brought back from a farm visit and cooked for lunch at kindergarten.

- Flowers and herbs having been grown and sold for Thanksgiving (the returns being spent at the ice cream parlour).

- Songs practised and then performed at an old people’s home to the pleasure of the elderly.

- Scientific insights being presented to an impressed audience, – or acrobatics or magic tricks.

- A game that has been crafted by the children themselves (possibly even invented by them) which then serves generations of kindergarten children to come.

- A hut made from sticks and branches in which the children can play the whole summer long,

- and so forth.

The possibilities are plentiful. Let us make sure that the children receive plenty of recognition in and outside of kindergarten. A “D” at school does not yield any social recognition, and even an “A” only appreciates the individual’s accomplishment while possibly hurting somebody else.

About 7:

Learning processes are most successful if there is a satisfying, possibly even inspiring, exchange of thoughts on the subject matter.

Even young gifted children are visibly perked up when they find adequate playing mates with whom they can have meaningful conversations. They need them from early on. There should be peers in age too, because the ability and desire to collaborate depends on early experiences:

Does it make sense to work together with the others or is it just one continuous frustration?

A good project can lead children of different talent and developmental status to mutual and satisfying success. The special Playing and Learning Needs of gifted children have to be observed though.

If you want to understand what it means if great differences in intellectual aptitude have to be “bridged” at all times, picture this: an adult with an IQ of 110 who, at his job, has to get along and carry on satisfying conversations with people who would score 30 points less in an IQ test.

If that is too abstract, imagine this: a 6 years old child never has other playing and learning mates than 4 years old children. What would that feel like? That is what a gifted child feels like if it does not have another gifted child in the group.

In the case of no playing mates of the same age we would not hesitate to act out of pedagogic considerations. Yet, we take the isolation of a gifted child as normal and inevitable.

At school the problem of inspiring conversations and sophisticated cooperation gets even worse. The gifted child will have such encounters even less often.

How thrilled were my daughters many years ago when they were enrolled at the CJD School in Brunswick and for the first time in their lives experienced that exciting discussions were carried out of the classroom into the school yard and continued there until the break was over. In many schools this never happens.

About 8:

Learning processes are most successful if another person supports the process with his professional as well as his personal authority and at best even with his own enthusiasm for a given subject matter.

This person could be the mother, the father, the grand-mother, the grand-father, the sister, the brother, a friend, a playing mate, a kindergarten teacher, a school teacher, a coach, a mentor.

I should like to call any of them a mentor. A gifted child needs one – or even better – several mentors.

In kindergarten we are at an advantage. We are not restricted by a fixed curriculum, but instead we are free to pick any interesting subject matter and introduce interesting activities and topics which we ourselves are interested in, which means we can make pedagogic use of our own enthusiasm.

What do I have to contribute to be a good mentor for a gifted child?

1.

I am still (or again) thrilled by my own learning processes.

2.

I have genuine pedagogic talent, which means, I still – even after 20 years – love exploring things with the children. I am not bored or bothered, but instead the children’s liveliness and desire to learn still inspires me. And the children like me, most of them anyway, and they want to emulate me.

The problem is this:

All kindergarten and school teachers, all mothers and fathers have gone through our school system and have acquired a more or less disturbed and troubled attitude towards learning. Some look at learning as if it were a punishment, new things are experienced as a menace and the challenge of intellectual effort is a nuisance.

That means, they have to get rid of some of such bad feelings before they can be good teachers for children.

In spite of all the difficult working conditions, the much too large groups and the shortages in personnel prevailing at kindergartens, I think it important that every committed kindergarten teacher allow himself to go with the flow of working closely along the lines of the children’s own pursuits.

To me this boils down to feeling entitled and taking it as a professional calling to regularly work in small groups. We should defend the right for intensive activities with the children with all we have.

A person is suited to be a teacher and mentor of gifted children if he/she plays, learns and teaches with enthusiasm and talent.

Do also read: Mrs Becker Stages an Opera

Do also read: Cognitive Advancement in Kindergarten. Gaining Knowledge, Practising the Act of Thinking – To be translated

Do also read: How Does Learning and Research Happen?

Addendum

After a professional discussion about this lecture, I was inspired to add another section:

What do children take away from offerings?

A chair circle topic or an activity in which an orange is cut up so that the children can smell it and experience that juice runs over their hands will hopelessly underchallenge some of the children, whereas for other children it is an essential experience in which they learn a lot.

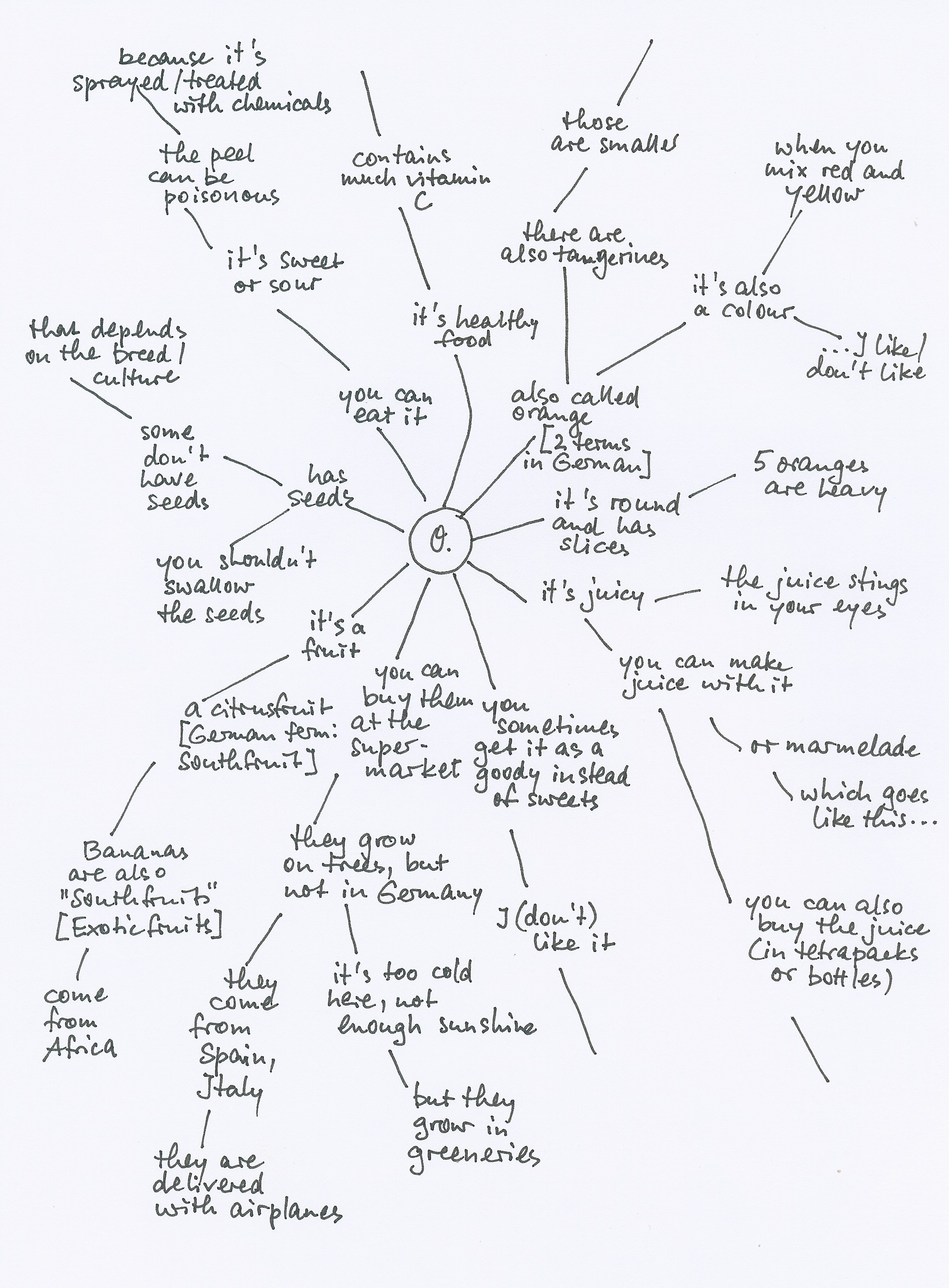

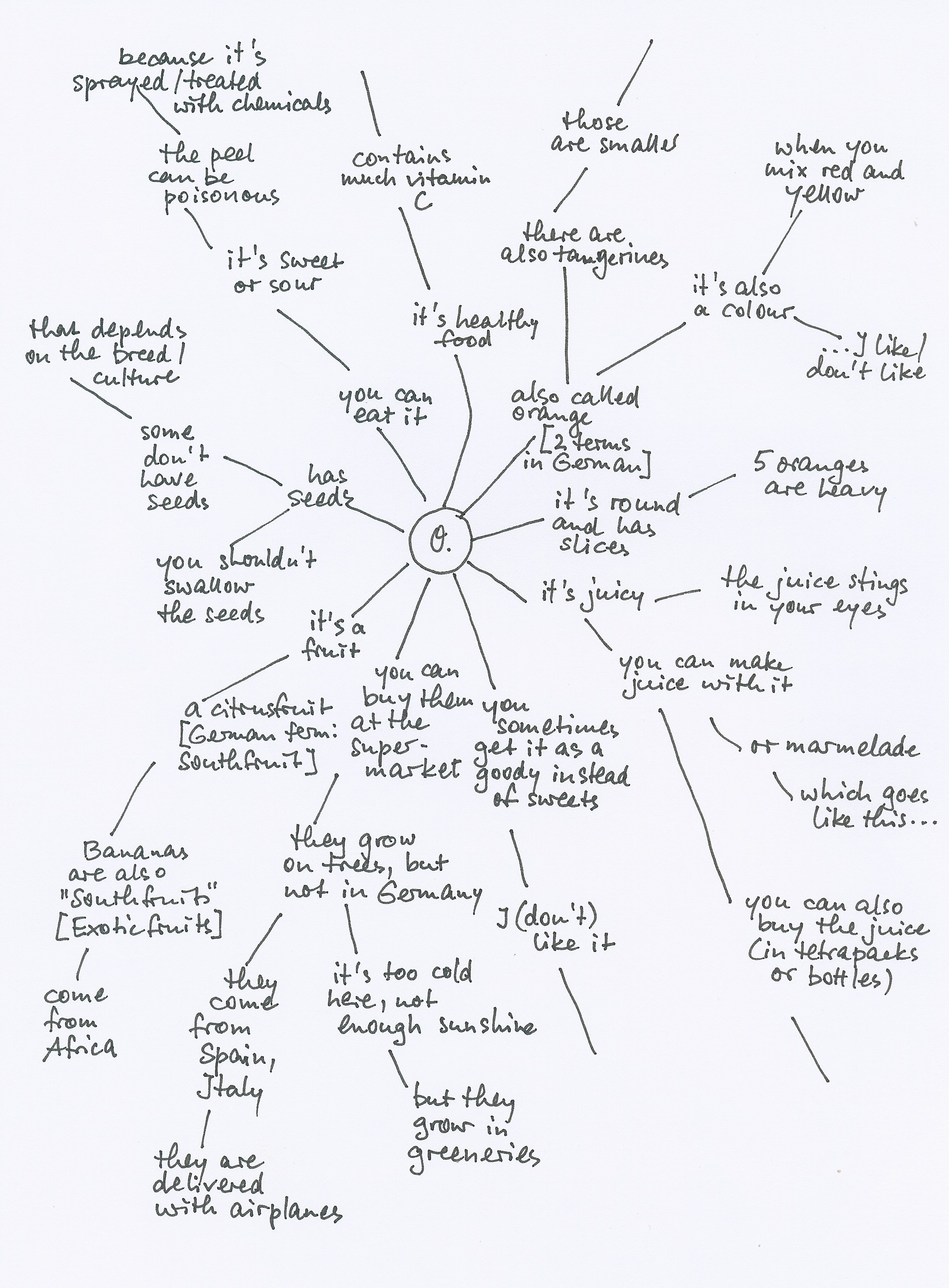

If one compiles what the children already know about oranges in a kindergarten group, the following picture can emerge:

Some children have very little knowledge, others almost all of the knowledge presented. The offer can also be enjoyable for a child who knows all this, knows and has already experienced a lot, but it hardly advances him or her.

So does it make sense to offer such experiences to the whole group? The more weakly developed children may be involved with all their senses and need some time to have some direct experiences with the orange.

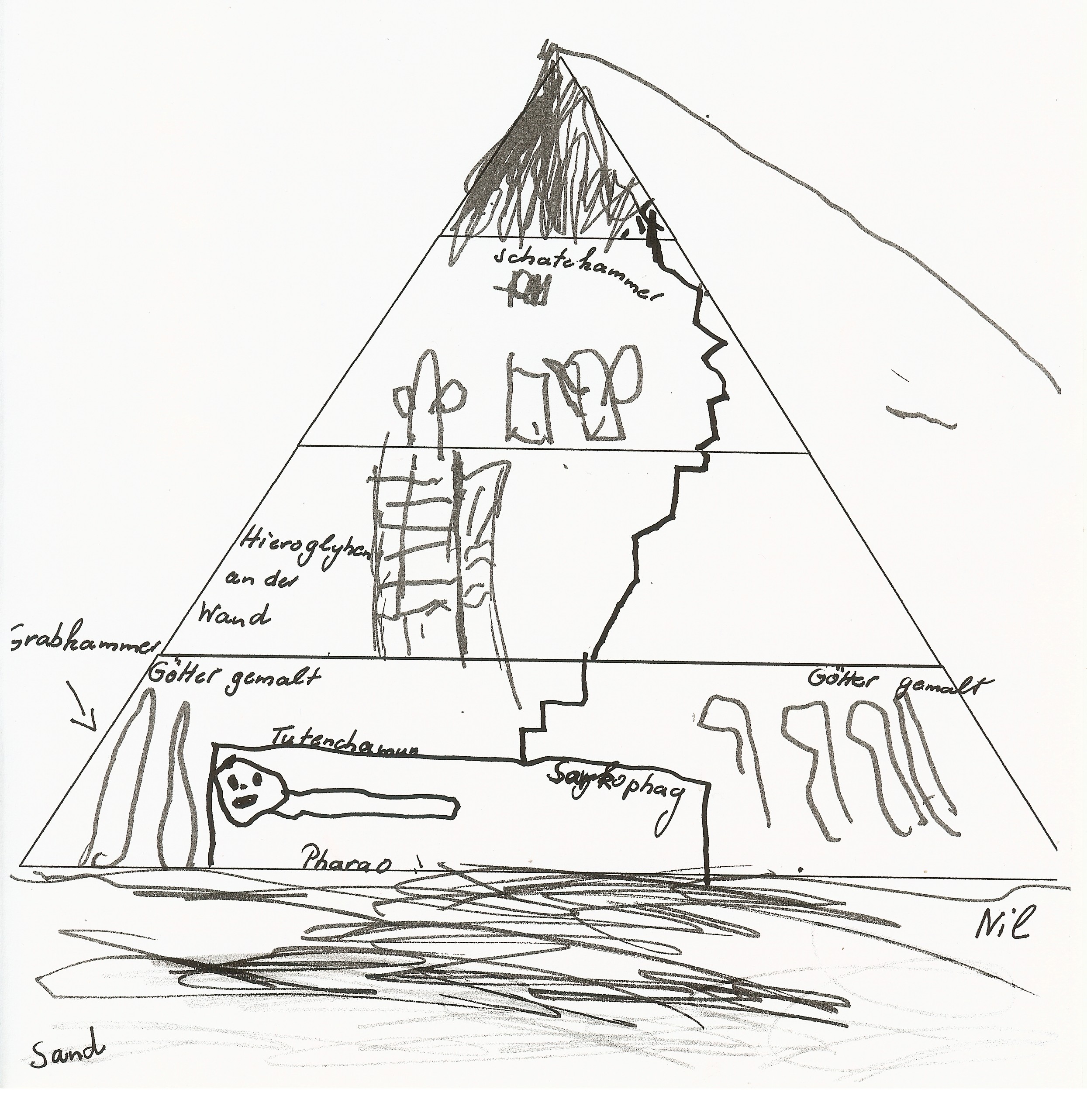

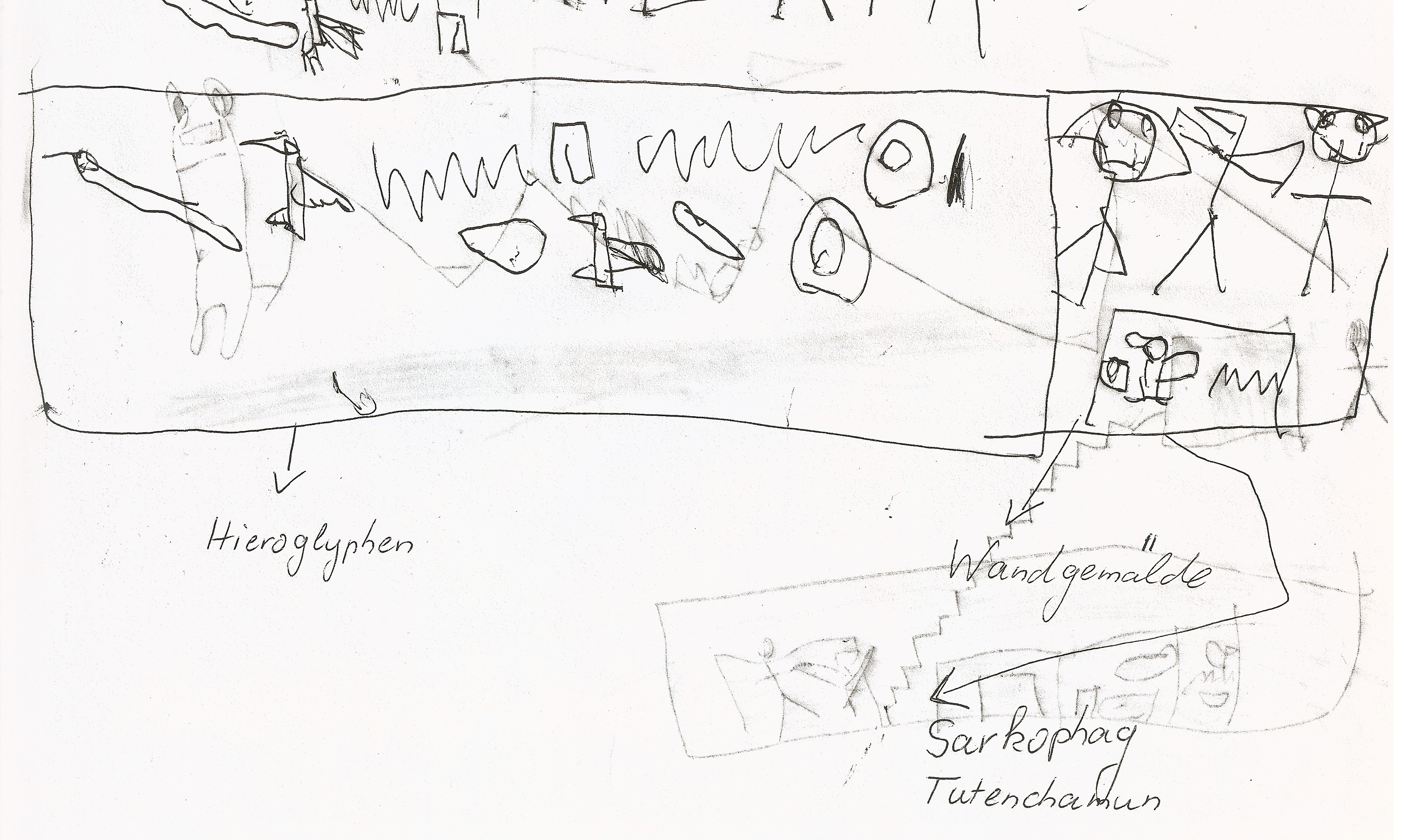

For particularly gifted and highly gifted children, this could also be a (short) introduction, but it has to go on quickly, they have to be able to recognise new things in order to satisfy their hunger for knowledge. So here you can move further out in the conceptual model orange (see illustration), in the ramifications that promise additional knowledge and understanding.

For these children, discussing concepts is also useful, such as healthy eating or transport routes for food, or imaginatively making up stories about the life of an orange or creating a picture book on one of these topics.

See also: Children Writing Picture Books.

Date of Publication in German: 2012, September / 2021, December

Translation: Arno Zucknick

Copyright © Hanna Vock, see Impress.

The translation of this article

was made possible by

Dr. Dr. Gert Mittring, Bonn, Germany.