by Hanna Vock

An article in the magazine ELTERN [Parents] from the year 2009 advises against checklists for determining giftedness. Even though the publication is not exactly current I deem it important to speak out on the topic.

The article states:

>Checklists for determining giftedness are fatal! / More and more parents and kindergarten teachers are wondering whether their child might be of outstanding talent, and they increasingly do so even with regard to the very youngest children.

ELTERN-Interview with expert Dr Eva Stumpf

Munich (ots) – 16 December 2009 – Giftedness is on everybody’s lips these days, notwithstanding that statistically it occurs in only one out of 50 children. Still an increasing number of mothers, fathers and kindergarten teachers ask themselves whether they are faced with a ‘super-talent’. The question whether this can be safely determined was the subject of a talk with expert Dr Eva Stumpf of the Information Centre for Giftedness, department of the University of Würzburg (01/2010 available today, feature topic: “That’s How Smart Your Child Is”).

„Any diagnosis made for a subject younger than 7 years is questionable. There are hardly any adequate test procedures for children that young”, explained the expert.<

And further:

… in a nutshell …

Our article deals with the idea that an early detection of giftedness is not only impossible but also hazardous. Such ideas, regrettably and to the disadvantage of many gifted children, are rather widespread.

In this our article we take a closer look at the set of problems pertaining to >detection with the help of checklists<.

Unfortunately, it is not mentioned in the interview, that a reliable test does exist, which has proven to measure an extraordinarily high IQ even with pre-school children: K-ABC (Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children).

Even if this test is not explicitly designed to measure intelligence far above average, it still provides valuable initial clues about the current intelligence level of a child.

Many years of experience have shown that – if applied professionally on the background of profound knowledge about giftedness AND substantial experience with gifted children –

in a follow-up testing at an older age with HAWIK, the trend of the earlier testing with the K-ABC is confirmed to a high degree. (See also the study done by the Max Planck Institute mentioned later.)

The HAWIK (Hamburg-Wechsler-Intelligenztest für Kinder; the respectively most current issue, the fourth being from May 2011) is an established and approved test procedure for children of 6 years and older, and it is perfectly applicable with regard to top performances. The HAWIVA (The HAWIK version for pre-school children) already having been released and used has been called back for revision by the authors to improve standardization (as of May 2011).

The application of a test is – as far as I am concerned – only one basis, and not sufficient at that, on which to determine giftedness at an early age. It takes more: a thorough interview with the parents as well as professional (evocative) observations over a longer period of time.

See: Modes of Observations

See: Standards for Conducting Diagnostic Test Procedures

See: Determining Giftedness

See: Recognizing by Observation

And what does research tell us?

In the magazine “Max Planck Forschung” [Max Planck Research] (3/2006 issue) Anne Goebel reported about the LOGIK-Study, which was initiated by the Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research in 1984 and completed by the involved scientists in 2005. In this longitudinal study the development of 210 subjects from their 4th to their 23rd year was examined. The research objective of the study was, roughly, to get a better understanding of the genesis (i.e. the emergence and evolution) of individual competencies.

(This is how the name of the study comes about: Lo ngitudinalstudie zur G enese i ndividueller K ompetenzen.)

Among other things, this study examined the development of intelligence as an individual feature and produced the following results, as introduced by Jan Stefanek of the Institute for Psychology of the University of Würzburg at a convention (quote from Max-Planck-Forschung, ibidem, p. 70):

>“Intelligence is relatively fixed rather early.“ Verbal as well as the non-verbal intelligence, as shown in the study, underlie 2-year-cycles of stability, which even grew stronger as the children grew older. „The differences in intelligence detected at the age of 4 years remained largely unaltered two years later”, said Stefanek.

In the following years this tendency even crystalized further. “… The results of the testing at the age of 4 render a predictability of the intelligence measured at the age of 6, which is significantly above average. And the values determined at the age of 6 then even allow for an accurate prediction of later intelligence.”<

The attachment and the scientific results can be found in: Schneider (publisher) Entwicklung von der Kindheit bis … [Development from childhood to …], see: Bibliography.

Are checklists fatal?

Upon having boldly denied the detectability of giftedness Stumpf warns us not to use checklists:

>Dr Stumpf also advises against the use of checklists as are in circulation and which are supposed to detect giftedness: “I consider these lists to be fatal! Indicators cannot be generalised. The only reliable indicator, pointing towards giftedness, is an extraordinarily early language acquisition. Such children speak 3-word-sentences at the the age of 1 year and in extreme cases they read philosophy books at the age of 4.”<

This reveals a rather simplistic view on giftedness, which could easily unsettle parents. If the child does not speak particularly early and extensively, parents might think the child is not gifted. However, experience shows that quite a few gifted people did not stand out early on with regard to language. Yet, in spite of their little urge to talk and their limited command of the language, their mental performance was remarkable – their vocabulary sometimes being impressive – so long as anybody bothered to actively take interest in their thoughts and their mental development.

Then again, language skills that draw attention should be observed and adequately furthered, yet these skills alone do not make for giftedness.

Then, under false assumptions, Stumpf goes on to give a pedagogically inauspicious piece of advice (quoted as in the mentioned ELTERN-article):

>If parents have a suspicion that their child might be gifted, they should wait and see. Says Dr Stumpf: “That is what most parents do anyway. They watch out for what their child shows interest in, and what input it requests, and then they try to meet it.”<

Wait and see! That’s what parents are frequently told by paediatricians, psychologists and pedagogues – sometimes with the addendum: “That’ll grow out.”. From my point of view it is wrong to stay passive and wait, it is even harmful to the children. And what’s more, the necessary input should not only be given by the parents but by the entire educational system, from kindergarten to university.

It is better to get into the matter, face the upcoming questions, get the relevant information about advancement of gifted children, and talk to the kindergarten teachers. It is no good to wait and see until the child finds itself in permanent frustration.

(See: Permanent Frustration.)

>If, on the contrary, a family gets fixated on “giftedness” too early, there may be a harsh awakening.< (ibidem)

Why should a family that suspects one of its children to be gifted become ‘fixated on giftedness’? A child is not defined by its degree of giftedness and even less by its performance. Parents know this, and they should be reassured in this knowledge at every single counselling session. The relationship between parents and children is usually much more complex and differentiated.

>Then all later problems at school are attributed to the assumed distinctiveness. And it is an enormous frustration when it turns out later that the diagnosis is unsustainable.<

Many gifted children do at one point or another have trouble at and with (German) school. To ascribe this to an early detection of giftedness appears helpless and unfair to parents and children.

The “enormous” frustration Stumpf is speaking of can only occur, if parents measure the value of their child by its intelligence and talent. That is fatal.

Giftedness is not about “better” but about “different”.

With regard to small children, this being different materialises as different playing and learning needs, which should be observed, so that the child may develop happily.

See: Special Playing and Learning Needs

There may be problems later, if the diagnostics of giftedness in earlier years were not conducted with the necessary care – or if the limited accuracy of the instrument ‘testing’ was not conveyed to the parents sufficiently – or if it was not explained to the parents that the threshold value for giftedness at an IQ-value of 130 was an entirely arbitrary matter of definition. All this is therefore vital to be observed in testing.

An entire part of chapter 2.1 in this manual is dedicated to recognising and observing. Pedagogues, knowledgeable and experienced with regard to the phenomenon giftedness, are very well capable of recognising giftedness and of responding adequately and creatively.

This is demonstrated clearly by the many examples from practical work, which always show both: support and better understanding. That is how, as in an upward spiral, the efficiency and quality of both processes can be raised.

When it comes to checklists, it is the same as with everything else: there are good and bad, useful and useless respectively. Furthermore the quality of the outcome is highly dependent on the person using the checklist.

The development as well as the use of checklists can be done in very unprofessional manner.

An Example:

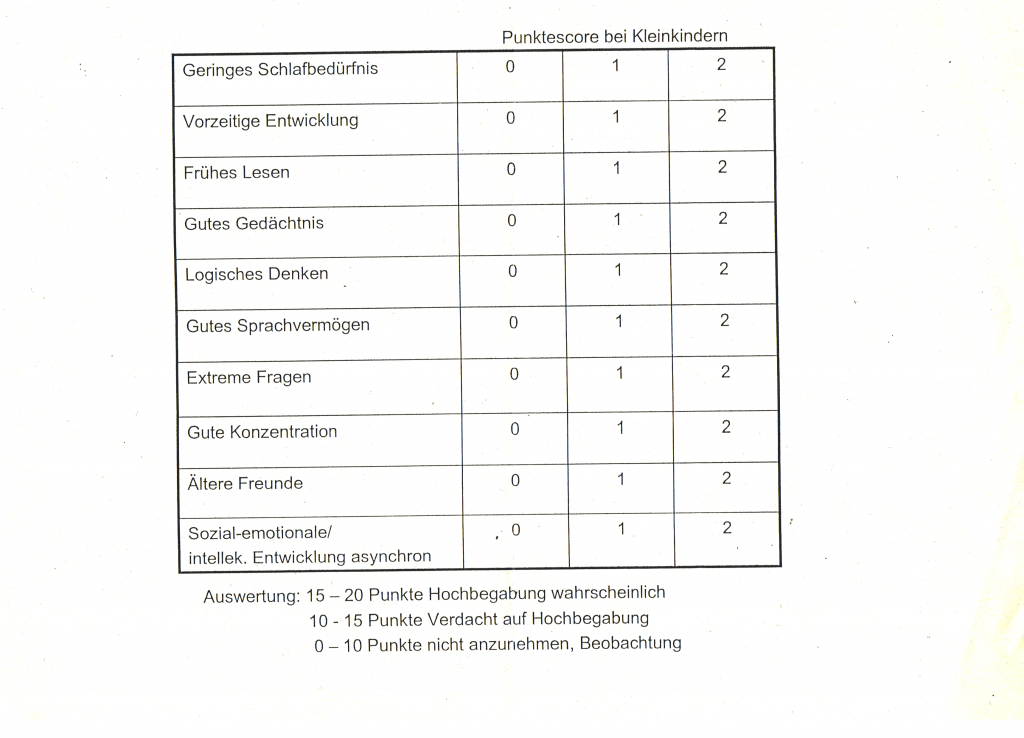

A paediatrician handed out the following sheet which they were to fill out and evaluate by themselves.

***

Caption:

(above the table:) Score Points for small children

(keywords from top to bottom:)

Little need for sleep

Premature development

Early learning

Good memory

Logical thinking

Good language skills

Extreme questions

Good concentration

Older friends

Socio-emotional/intellectual development asynchronous

(below table:)

Evaluation: 15 – 20 points giftedness likely

10 – 15 points giftedness suspected

0 – 10 points giftedness not to be assumed, further observation

***

But this checklist is a useless instrument …

-

- because it contains too few items to describe giftedness,

- because the keywords are not being explained as to what they really mean,

- because it leaves it up to the parents to decide what an “extreme question” is for a 3- or 5-year-old.

Let us imagine a 3 years old child …

– that likes to sleep (and gets 0 points)

– that is interested in numbers but still wets its diapers and mostly needs help getting dressed (which is why the parents give it 0 or 1 point for “premature development”

– that does not read yet (0 points)

– that does have a very good memory, which the parents happen to consider normal (giving it 1 point here)

– whose outstanding logical thinking is recognised (2 points)

– that does not speak correct grammar and whose articulation maybe even a little unclear (0 points)

– that does occasionally come up with some rather extreme questions, but nobody takes the time to get to the bottom of them in a conversation with the child, nor does anybody dispose of the skill to do so. What, for example, is to be said of the question of a 3-year-old: “Do people die when they get 18 feet tall?” If this question is dismissed as childish nonsense, the intellectual implications of such a question are not recognised (and there may be only 1 point given here)

– that does not have any older friends, simply because there are not enough older children around (0 points)

– whose intellectual and socio-emotional development are quite in accordance with each other, which incidentally is very hard to assess and is frequently subject to misjudgement. But simply because their child’s socio-emotional development does not arouse any attention, the parents give 0 points here.

This child would score an entire 4 to 5 points, and the parents would presumably dismiss the idea their child might be gifted altogether – to the disadvantage of the child.

There are also checklists to be found on the internet, which have been drafted by parents themselves. These are meant to be helpful, but often they basically describe those parents’ child as opposed to detailing general features of high ability. Such lists may be misleading for other parents.

A good checklist can be helpful

With our Indicators of Possible Intellectual Giftedness (in connection with the provided examples) we have aimed to compile indicators that are based on experience. In our courses these are being exemplified and in our manual we try to illustrate them with a variety of case studies taken directly from practical work experience in kindergartens.

In contrast to Dr Stumpf we are of the opinion that it is possible and important to generalize the individual and rather diversified indicators of giftedness, as shown by children, and extract thereof a useful set of characteristics which strongly point towards giftedness even in pre-school children.

Published in German: 2011, July

Translated by Arno Zucknick

Copyright © Hanna Vock, see Imprint

The translation of this article was made possible by

Brigitte Gudat, Eschweiler, Germany.